As you all know by now, I firmly believe that London has become one of the best food cities in the world, boasting a huge diversity of cuisines as well as an incredible array of award-winning restaurants.

But just a few short years ago, London was mocked for its drab, boring cuisine – the culinary manifestation of a Puritan ethic that regarded the spending of anything more than necessary on food as just plain wrong. The self-denial cultivated by Protestantism yielded bland, dismal renditions of dishes that could have been (and, competently prepared, can certainly be) delicious: Bangers and Mash, Toad-in-the-Hole (sausage and sometimes kidneys) baked in Yorkshire Pudding Batter…Pork Pie (mmm, innards)….Fish & Chips (often greasy)….well-done (very well-done) Sunday Roasts with the drippings utilized on wash-day Monday to bind leftover potatoes and cabbage into dinner patties called Bubble & Squeak.

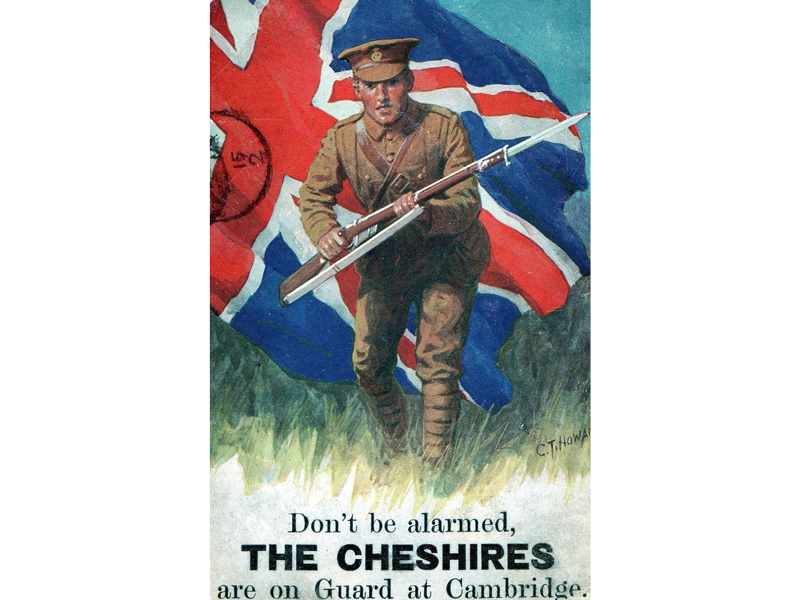

Then came World War I. Artisanal farmers and dairymen abandoned their fields and flocked to the cities to work in factories. Artisan cheese all but vanished. France, Italy and Spain held on to their peasant culture and set up Appélations Controlées to protect their unique ingredients. (Today Britain has only one: Stilton Cheese.)

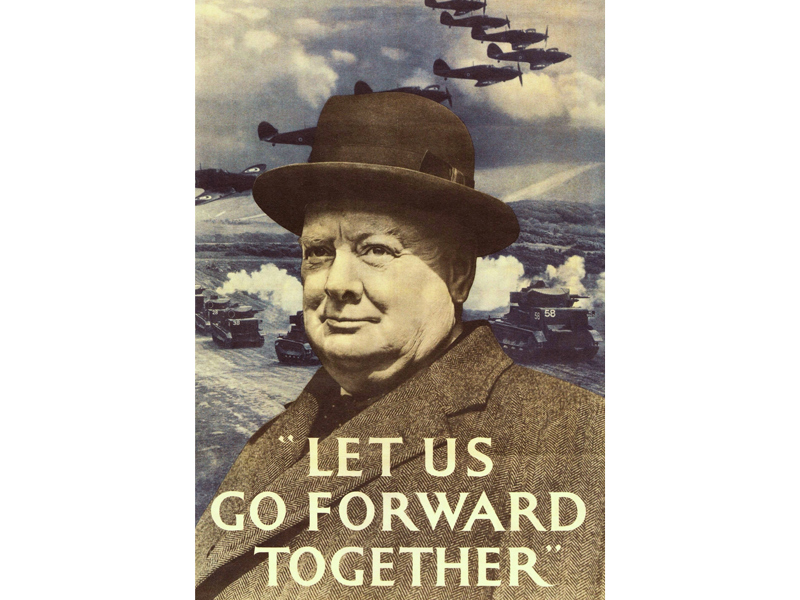

And if that weren’t enough damage to British food, World War II hit the country with a double-whammy because England imported roughly 70% of its food and Germany intended to starve the Brits by sinking their shipping convoys. England was locked in a war of national survival.

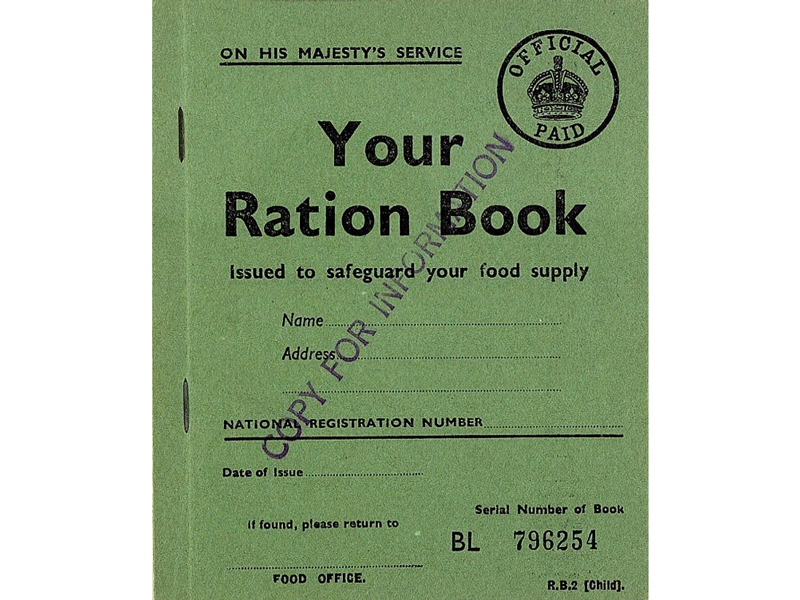

The best and most nutritious food needed to be allocated to the troops. Consequently, rationing was introduced to the folks on the home front on a vast scale. A typical weekly food ration for an average adult was 4 ounces of bacon, 2 ounces of cheese, a single egg, and 8 ounces of sugar. Rubber, paper, metal pots and pans, and even bones were collected on a regular basis from households.

BTW the fat content from a single pork bone could supply an explosive charge for two rounds of ammunition (and here you thought the risk of pork fat was limited to heart attacks).

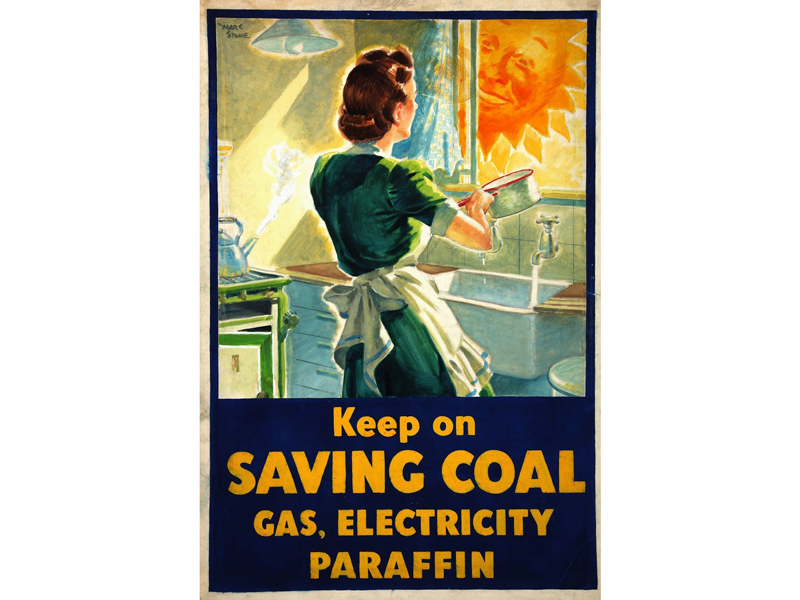

Mothers and housewives were forced onto a

wartime footing in the kitchen. The British diet changed forever and homemakers

were severely challenged to put nutritious meals on the table without the

protein they were accustomed to using. It was all about making do with less.

Factory workers would come home to a nutritious dinner of Woolton Pie, a casserole of root vegetables in white sauce smothered with a thick layer of mashed potatoes. Black Pudding (blood sausage) was not rationed, nor were organ meats apparently, because Haggis – an assemblage of liver, sheep’s lungs, heart and tongue, ground up and baked in the lining of a cow’s stomach – assumed a new popularity.

Chicken livers on toast become a staple, as did kidney pie. Spam found its way to the breakfast table, and smoked cod ended up in a potato-like chowder called Cullen Skink. (Cullen is a town in Scotland. I don’t know about Skink.) With sugar tightly rationed, Apple Brown Betty became Britain’s go-to dessert because the apples provided the needed sweetness.

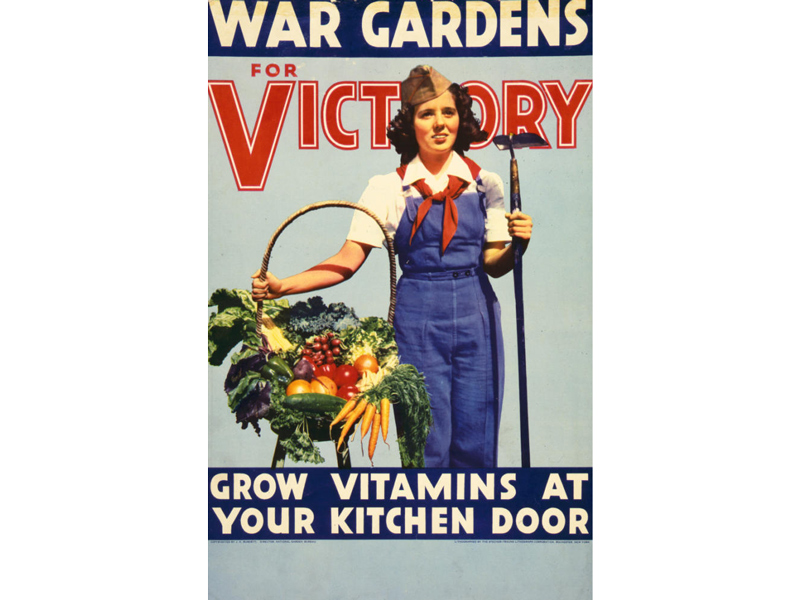

Victory Gardens sprung up on every little plot or scrap of available land…even directly in front of the Prince Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens. And women took to fruit and vegetable canning on a massive scale. Kraft Cheesey Pasta that was ‘cheese-flavored” was a thrifty choice.

In fact, when I saw the image of the Cheesey Pasta, I recalled my own somewhat vague childhood memories of the war, because in our house the same Kraft product was called Kraft Dinner. Growing up in a house with three families, I recall my mother and grandmother feeding us Mac & Cheese quite often. It must have run five cents a person.

I also recall, as a five-year-old, rummaging through a kitchen drawer on the hunt for ration stamps emblazoned with mighty tanks, warships, cannons and fighter planes. With a fistful of stamps in hand, I’d sneak off to my room and carefully arrange them on the linoleum floor. Most kids who stole those valuable stamps would have received a ration of punishment. But for little Phil, living in a house with three women (my grandmother, my mom and my Aunt Rose), the best they could muster was, “Isn’t little Phil cute?”

Another wartime frugal dish that my mother fed our extended families was Beans and Dumplings. If memory serves me right, it combined the taste of water with the flavorful touch of flour.

Back to England.

There were weekly drives in the neighborhoods to

collect items for the war effort – even bacon grease. But not all animal

products were gathered. Rabbits, which bred year ‘round, were a plentiful

source of meat, and many Brits built rabbit hutches in their backyards. Chicken

coops, too. Pig Clubs were also established. Neighborhoods would pool their

money and buy a pig, fatten it on scraps of food, and eventually butcher it.

Nothing went to waste.

Rationing was finally retired in 1954. By that time, British food culture had sustained major damage; an entire generation forgot how to cook. Food in Britain was stunted.

And then. AND THEN!!!

Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister in 1979, and the boom that followed solved the problem. Suddenly it was okay to have money and to spend it. Dining out became acceptable, not sinful.

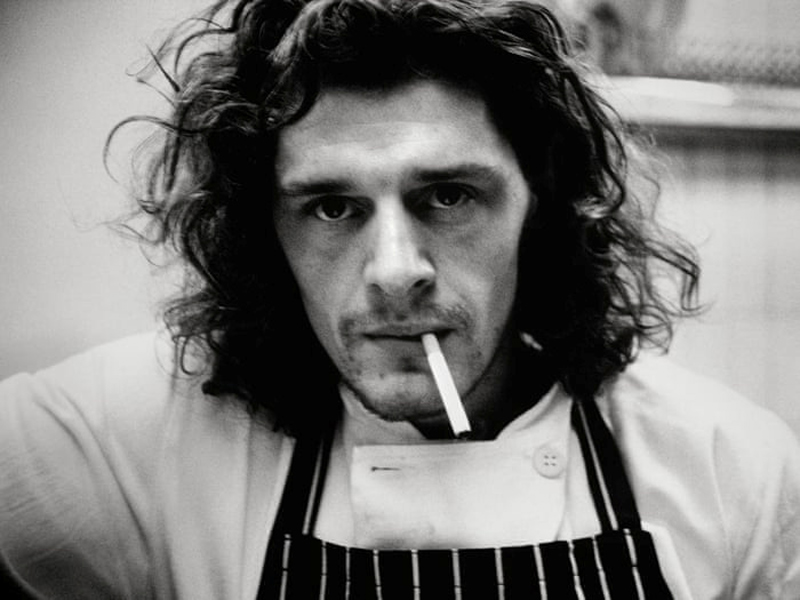

The enfant terrible chef, Michael Pierre White, opened HARVEY’S and was awarded two Michelin stars. LE CAPRICE arrived on St. James Place. And LE TANTE CLAIRE was crowned with three – count ‘em, THREE – Michelin stars. After Le Tante Claire closed in 2004, Gordon Ramsay opened in the same spot on Hospital Road.

London was suddenly becoming an outward-looking

global city. RIVER CAFÉ was, and still is, enjoying Michelin star-studded

reviews. QUAGLINO’S arrived with great fanfare. And the world-renowned

designer, Terrance Conran, resurrected Bibendum in Kensington – still going

strong today with Claude Bosi in the kitchen, fine dining (crazy expensive fine

dining) upstairs, and an oyster bar, serving giant pristine shellfish platters,

on the ground floor.

Joanne and I prefer the oyster bar.

W.T.F.

PHIL

very nice thank you