I’ve always been a little fuzzy about the distinctions among French eating establishments. Am I eating in a brasserie or a bistro or a restaurant?

BRASSERIES originated in the Alsace region, right next door to Germany, but are now found throughout France. Traditionally they offer all-day, non-stop service, including breakfast, and are typically open late. Most are large, informal and lively. And – in line with their Germanic roots – beer is often made on the premises. Menus are more expansive than what you’ll find at a bistro. They feature hearty traditional French comfort food like coq au vin, boeuf bourguignon, steak frites, and almost always a huge variety of fresh oysters. More often than not, they’ll also feature the Teutonic classic, choucroute garni – mit sauerkraut und grain mustard.

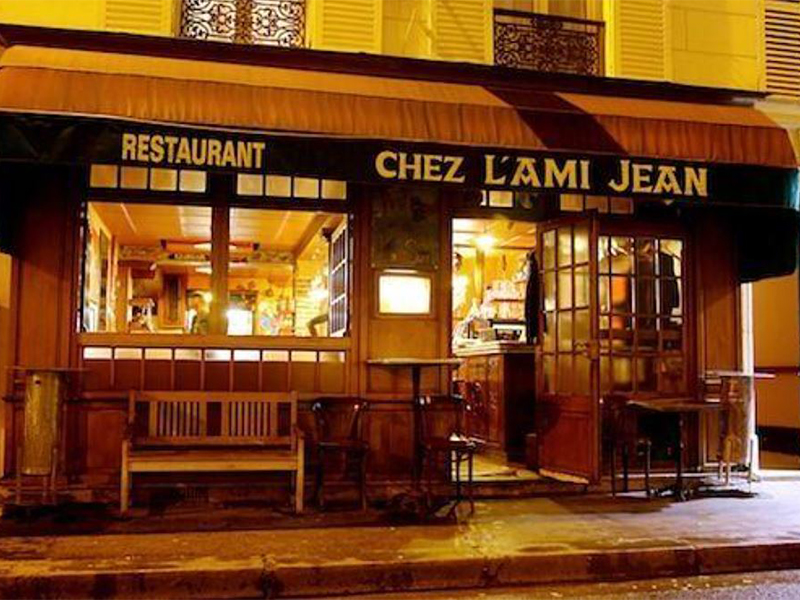

BISTROS are usually cozy and informal, intimate and neighborhood-y. They’re traditionally family run, with smaller menus that focus on simple, home-style Frenchy cooking. Offerings can vary from day to day depending on the season and whatever’s freshest at the local market. Consequently, menus are often written on a chalkboard. Bistros are open for lunch and dinner only and often close between meal periods.

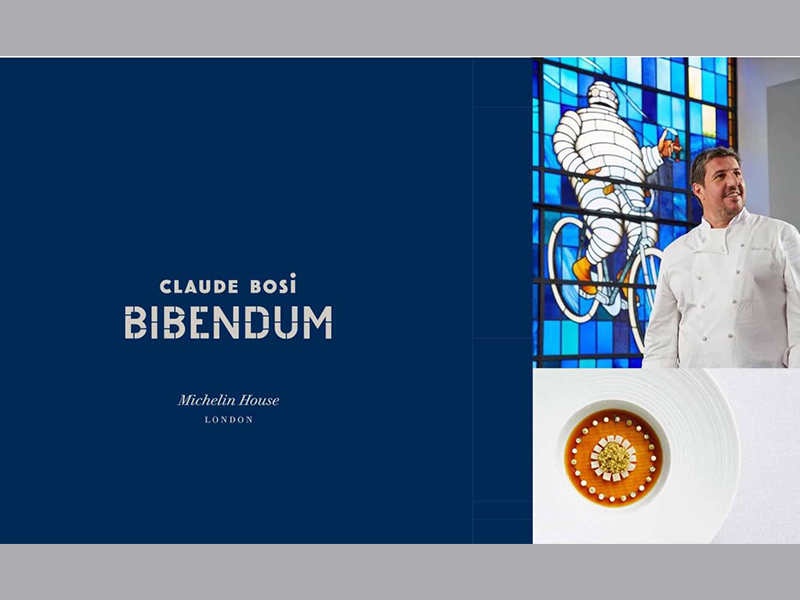

RESTAURANTS are, for most French people, occasion establishments – what we in the industry call “destination dining.” They can be resolutely traditional, spare and chic, or dripping with opulence. But, in the end, they’re sophisticated, quiet, and more formal, both for customers and staff. They often have set hours for lunch and dinner, and their menus are usually more extensive than bistros or brasseries. Plating is carefully considered and often a visual feast. Service is smooth and often chi-chi. Same for the bill.

The distinctions among French eating establishments have always been rather rigid, but these days the differences can be difficult to discern. Some brasseries have culinary aspirations equal to most any restaurant. Some bistros really should be classed as restaurants.

So, with all that in mind, I began to think about why there are almost no French chain restaurants in America. Certainly, there are a few. LA MADELEINE is a casual French bakery and café with several dozen locations, primarily in the southeastern and southern states. But that’s about it for the big operations. The last time I checked, Nation’s Restaurant News listed not a single French restaurant in its annual Top 100 Listing of chain restaurants.

Among the more notable smaller chains, PASTIS comes to mind. It has two locations in New York, as well as ones in Miami, Washington and Nashville. The genius behind them is KEITH McNALLY…and he is a genius.

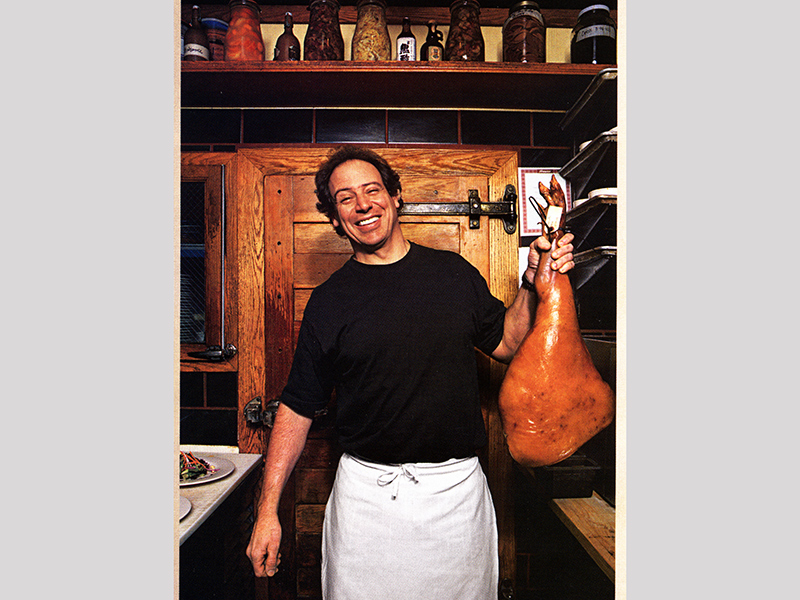

But we can’t talk “genius” without mentioning RICHARD MELMAN. Among too many successful restaurants to count, he created MON AMI GABI in Chicago. Now there are at least five, including the big and beautiful Mon Ami Gabi in Las Vegas.

So what’s the deal? There are countless Italian restaurant chains in America – OLIVE GARDEN, BERTUCCI’S, MAGGIANO’S, and even our own PARASOLE creation, BUCA DI BEPPO. Why only a scant handful of French?

Well, we need to talk about differences in culinary culture.

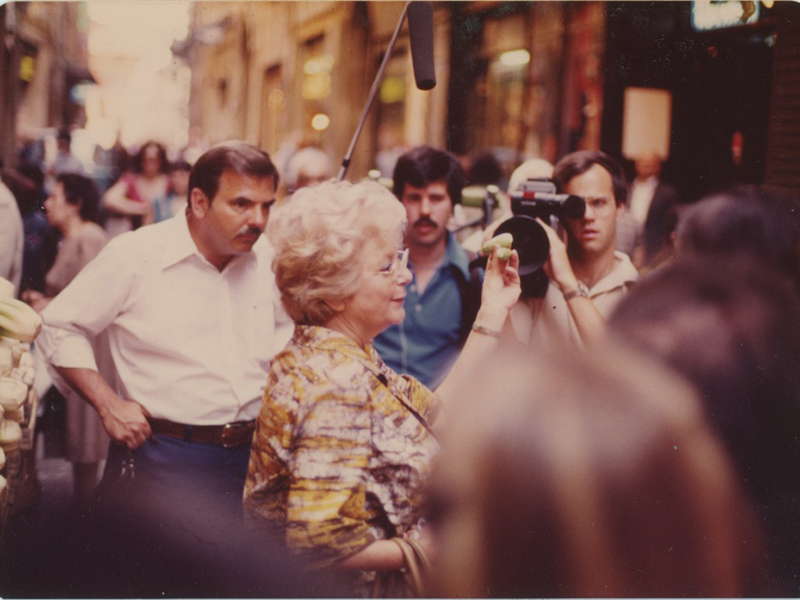

When I attended culinary school in Italy under Marcella Hazan, she drilled into my brain the difference between French cuisine and Italian cuisine. ITALIAN is straightforward, with simple cooking techniques using the freshest and best ingredients. It’s cooking with love, from the heart. Improvisation is okay…even encouraged. But because it’s simple, Italian is fairly easy to cook consistently, even at scale.

Her take on FRENCH FOOD? No surprise here. “It’s overly complicated and much too fussy. Too many sauces”. Marcella dismissed it with dispatch, and I think I detected a sneer as she did so. I also recall her reminding us that it was an Italian noblewoman, Catherine de Medici, who taught the French how to cook when she became that country’s queen.

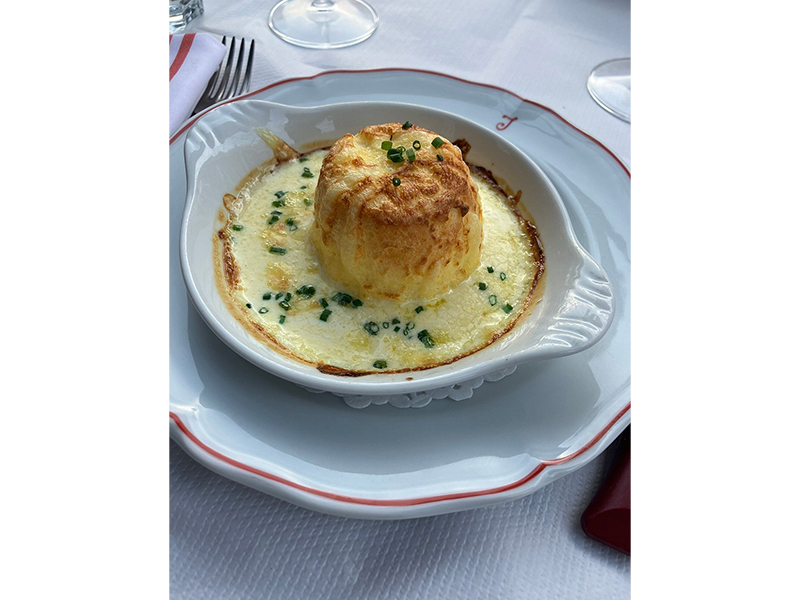

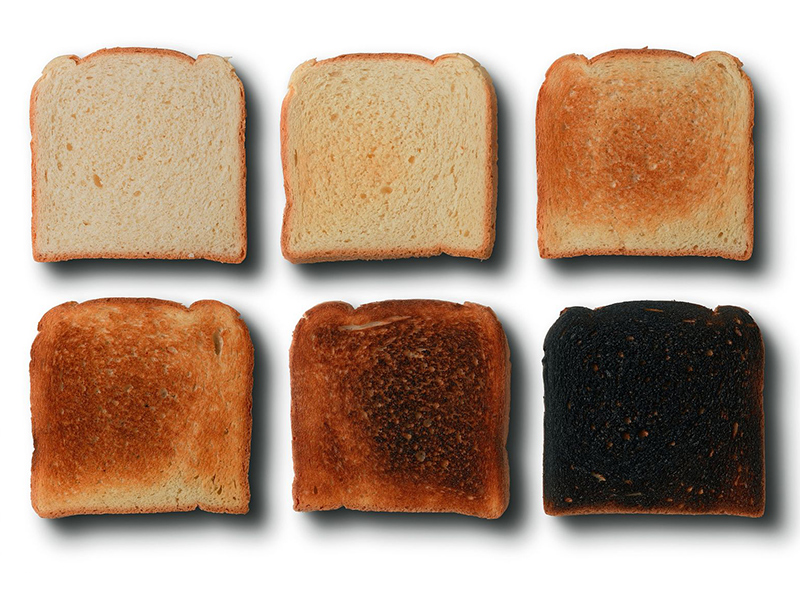

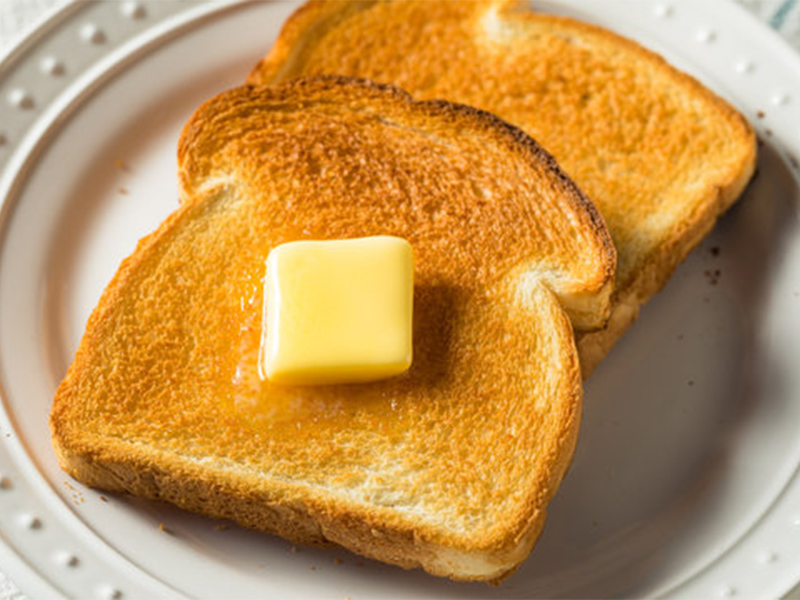

Marcella might not be right on all counts, but you can’t argue that French food emphasizes meticulous TECHNIQUE. Precise execution is de rigueur. And it’s not just the freshest local and seasonal ingredients that French chefs prize. They love the most expensive ones – lobster, prime cuts of beef, truffles, saffron, foie gras, superior heavy cream (which adds depth to sauces) and high-butterfat French butter, with its decadent flavor.

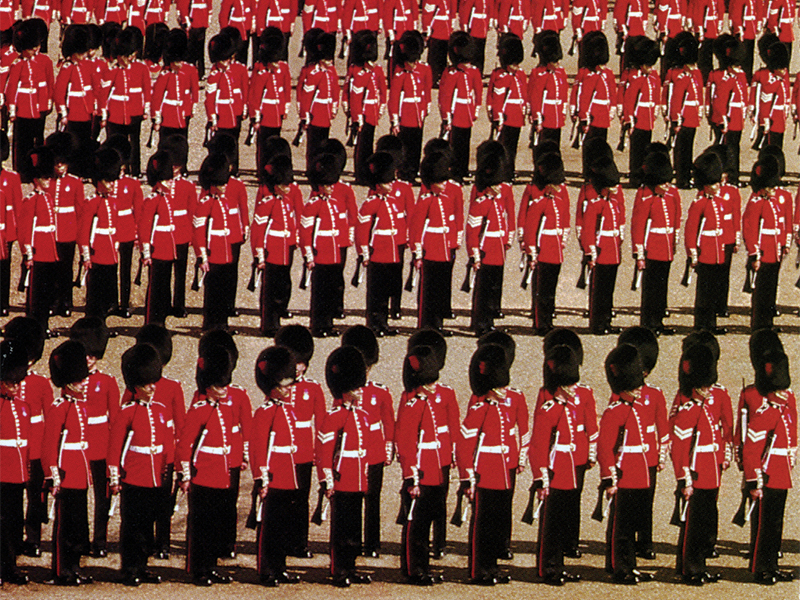

But it doesn’t stop there. Add to these premium ingredients the SKILLED LABOR required to render the classic French dishes. It requires years of training. For example, the kitchen service begins with the preparation of the five “MOTHER SAUCES” – BECHAMEL, ESPAGNOLE, VELOUTE, TOMATO and HOLLANDAISE. Several steps are required to make each of them, and success depends on patience, skill and precision, along with a deep understanding of culinary science. They’re called mother sauces for a reason; they’re the building blocks of countless additional sauces. Think DEMI-GLACE and MOUSSELINE. Oh, yes…NO IMPROVISATION!

So, there’s your answer. French food is much more complicated, with sky-high food costs as well as labor costs that reflect the need for a highly skilled brigade of kitchen staff. With the myriad steps required to prepare each dish (it takes forever even to learn how to make a proper French omelet), there is vastly more room for error along the way…resulting in lousy food.

That’s why, my friends, that there are only a few folks in this nation who can effectively manage multiple French food restaurants. I’ve already mentioned two people who can – Keith McNally and Richard Melman.

And I am compelled to say, that French cuisine, when well-prepared, is absolutely wonderful…especially the SAUCES.

Which causes the French to say, ”WITH THE RIGHT SAUCE, YOU CAN EAT YOUR FATHER.”

WTF,

PHIL